I think you’ll agree with me when I say: HSC Creative Writing is REALLY hard. How do you even come up with a creative writing structure or techniques?

It’s hard to think of an idea and it’s hard to know whether what you’ve written is any good.

Or is it?

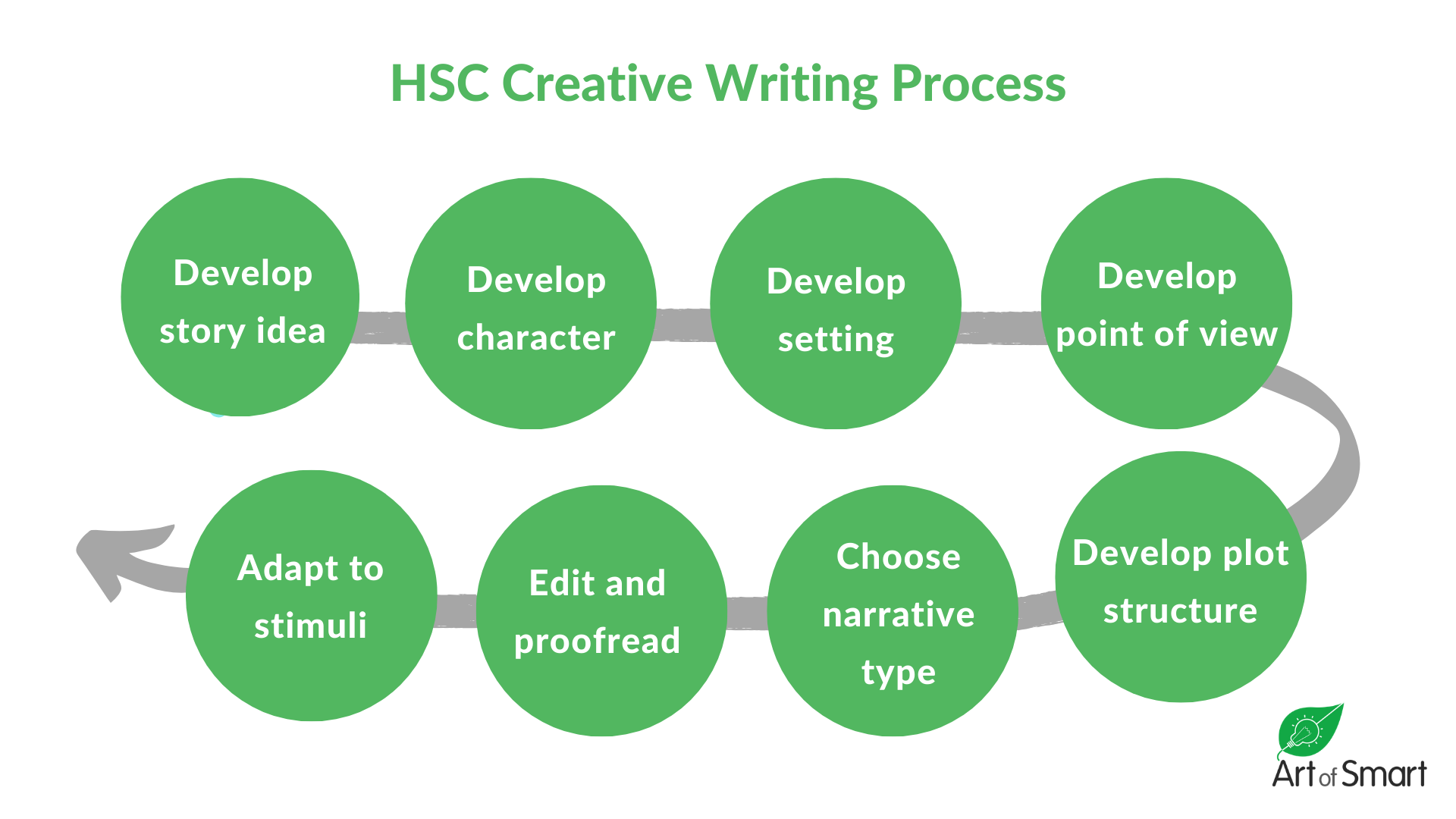

Well, it turns out there’s a simple, proven formula for writing a Band 6 story – and it comes in 8 easy-to-follow steps!

In this article, we’re going to walk you through each one so that Module C becomes less of a nightmare and more of an ace up your sleeve.

Let’s get started!

What does the Module C: Craft of Writing rubric say?

Step 1: Develop Your Story Idea

Step 2: Develop Your Character

Step 3: Develop a Setting

Step 4: Develop Your Point of View

Step 5: Using A Formula To Write A Band 6 Plot

Step 6: Pick Your Narrative Type

Step 7: Edit and Proofread Your Piece

Step 8: Adapt your Piece to Exam Stimuli

What does the Module C rubric say?

Most students sit down and try to develop an idea for creative writing without first thinking about what Module C is about and then struggle to mould their story to the stimulus in the exam.

The result? A story that often doesn’t convey anything much in a meaningful way that nails the marking criteria for the HSC.

Here’s the point.

The marking criteria for HSC Module C creative writing to score a Band 6 requires you to:

‘…consider purpose and audience to carefully shape meaning.’

Let’s put some emphasis on ‘carefully shape meaning’. Writing your story, and then trying to ‘stuff’ Meaning into it, just won’t cut it.

To “carefully shape meaning” refers to the deliberate and thoughtful construction of your narrative to convey a specific message, theme, or emotional response to the reader.

It involves making conscious choices about language, structure, and literary devices to effectively communicate your intended meaning.

So… how do you do that?

Step 1: Develop a Creative Writing Idea

In our work with thousands of Year 12 students over the last decade, the #1 mistake we see students make over and over again when it comes to creative writing is this:

Starting the writing process by brainstorming a unique story idea.

Now you might be thinking – isn’t that exactly what you just said to do? Doesn’t writing a great story start with a great idea for the story?

Well, no!

Trying to come up with a great idea for a story out of thin air from the very beginning places a lot of pressure on you to have that ‘moment of inspiration’ and the reality is that (as you may have discovered) this can be almost impossible!

A great story starts with a great character.

How should you develop your story idea then?

Skip to Step 2 and come back to this step-by-step framework on how to come up with a great creative writing structure that’ll impress the HSC exam markers and meet the marking criteria!

Here’s How to Develop Your HSC English Module C Creative Writing Idea.

Step 2: Develop Your Character

So, a great story starts with a great character.

But how on earth do you create a great character?

Creating a normal character sounds hard enough. But a great one? Man, this sounds really hard.

The biggest mistake students make when trying to create a great character is trying TOO hard and writing about things you haven’t 100% planned out.

So, all of a sudden, your character becomes this epic person, who is a cross between James Bond and the Hobbit, living in Elizabethan England. OK… that might be an exaggeration, but you get the point.

So how do you create a great character that works?

Here’s where there’s good news. There is a proven process you can follow to write believable characters that the likes of Pixar and Disney use to craft characters worth remembering. And we’ve broken it down for you!

Here’s How to Develop A Character for HSC Creative Writing.

Step 3: Develop a Setting

So you understand how to carefully create meaning for your HSC Creative Writing piece. Tick.

You’ve got a sophisticated character. Tick.

Now, in what setting and context do they live? Where will your story take place? When?

The moon? Ancient Rome? The Amazon? Your local area?

The biggest mistake students make at this step is simply making up the setting and context as you go (guilty!)

Do you think Disney makes up their setting and context for their stories as they go? No way!

Whatever setting you have it needs to:

- Be intentionally chosen and planned

- Be something you are familiar with and can write about well

- Be consistent with your character

- Be flexible to fit with varied stimulus material you receive in exams

So how do you pick setting and context?

Making decisions about the setting of your story has a lot of layers to it. Where is the story set? When? What was going on in that time period? What did people wear? What was the culture like?

Here’s How to Develop A Setting For Your HSC Creative Writing Piece.

Step 4: Develop Your Point of View

Which one is better?

- My journey to the shops was made much less enjoyable by the sweltering heat. I was feeling light-headed and faint.

- Your journey to the shops was made much less enjoyable by the sweltering heat which forced you to become light-headed and faint.

- Jennifer’s journey to the shops was made much less enjoyable by the sweltering heat which forced her to become light-headed and faint.

Get this:

It was a trick question…

Writing in 1st, 2nd or 3rd Person can all be great – it depends on the type of story, the number of characters, and what you are trying to achieve.

I’m going to take a bet though. You probably don’t even think about which point of view to write in. When you start, you automatically write in the POV you feel most comfortable in.

Sound like you?

Pixar intentionally chose Marlin’s POV in Finding Nemo — not Nemo’s. This wasn’t an accidental decision, it was an intentional one…

It all boils down to this – when you choose your POV:

- You need to choose it intentionally

- You need to evaluate which POV will be most flexible with different stimulus type

- You need to consider how many characters you have and which POV supports dialogue

- You need to consider which POV enables you to get inside your characters head and whether this is critical

So, how do you choose a point of view for your HSC story?

Not sure whether to go with 1st person, 2nd person or 3rd person? Each point of view has different pros and cons depending on the structure of your plot, and the number of characters you have. Have you chosen the right one for your HSC creative writing story?

Here’s Selecting A Point of View for HSC English Creative Writing.

Step 5: Using a Formula to Write a Band 6 Plot

OK, I know what you’re thinking.

We’re at Step 5 and I still haven’t got a plot or story idea yet. What on earth is going on?

Now that you’ve laid the foundation of your story, it’s FINALLY now the time to develop your plot. And because you’ve laid the foundation, creating a great story idea is going to be much easier.

So what’s the secret?

All great stories have the EXACT same plot structure.

It’s called the 5 Point Plot Structure:

- Inciting Incident

- Rising Action

- The Conflict

- The Climax

- The Resolution

So how do you use this structure to come up with a story?

To take your basic 5 Point Plot Structure and turn it into a story that’s going to earn you a Band 6, there’s a lot to consider.

Here’s How to Develop Your Story Idea for HSC English Creative Writing.

Step 6: Pick Your Narrative Type

Okay, so we’re at Step 6 – surely we’ll be putting pen to paper soon… right? Wrong!

First, you need to pick what narrative type you’ll be writing.

I can hear you asking: ‘But aren’t we just writing a short story?’

Well sure, you can write a short story, but the HSC Creative Writing PIECE can take any form you’d like – a monologue, a letter, or anything else that takes your fancy!

Writing something other than a short story also helps you stand out from the competition and impress those HSC markers!

So how do you choose a narrative type?

You get some help from Art of Smart of course! Read our in-depth article on picking a narrative type that will help you get that Band 6 here:

Here’s How to Pick a Narrative Type for your HSC Creative Writing Piece.

Step 7: Edit and Proofread Your Piece

Finished your first draft? Perfect! But this is the most important step, so don’t skip it!

I’m about to teach you the easiest way to get extra marks in HSC Creative Writing.

Editing.

Believe it or not, there’s an art to editing and proofreading that could push your mark right up!

We’ve boiled it down to 4 simple steps…

- Read your piece out loud

- Show – Don’t Tell!

- Short and Simple

- Less is more

To find out how to use these steps to do a killer edit of your piece, check out our article below.

Here’s How to Edit & Proofread Your HSC Creative Writing.

Step 8: Adapt your Piece to Exam Stimuli

Congratulations! You’ve got a KILLER HSC Creative Writing piece under your belt.

Trust me, that hard work is going to pay off in the HSC Exam!

“But how can I possibly adapt my story to the question they throw at me in the actual exam?!”

We’ve got you covered.

Here’s How to Adapt Your HSC Creative Writing Piece to Exam Stimulus.

Then, guess what! You’re done with your HSC Creative Writing Piece – and most likely earned a Band 6 in the process!

Really want to nail that HSC Creative Writing Piece for HSC English?

We have an incredible team of HSC tutors and mentors who are creative writing experts!

We can help you master HSC English creative writing and ace your upcoming HSC assessments with personalised lessons conducted one-on-one in your home or at one of our state of the art campuses in Hornsby or the Hills!

We’ve supported over 8,000 students over the last 10 years, and on average our students score mark improvements of over 20%!

To find out more and get started with an inspirational HSC English tutor and mentor, get in touch today or give us a ring on 1300 267 888!

Elizabeth Goh isn’t a fan of writing about herself in third-person, even if she loves writing. Elizabeth decided she didn’t get enough English, History or Legal Studies at Abbotsleigh School for her own HSC so she came back to help others survive it with Art of Smart Education. She’s since done a mish-mash of things with her life which includes studying a Bachelor of Arts (Politics and International Relations) with a Bachelor of Laws at Macquarie University, working for NSW Parliament, and writing about writing.