Wanting to nail HSC Physics Module 1: Advanced Mechanics with some circular, gravitational and projectile motion practice questions?

You’ve come to the right place!

We’ve created practice questions for all three topics in the Advanced Mechanics module:

- Projectile Motion

- Circular Motion

- Gravitational Motion

Notice number 3 is just the combination of 1 and 2!

In this article, we’ll develop your solving strategy and work through a bunch of sample questions in Advanced Mechanics.

So, what are you waiting for? Let’s jump straight in!

Advanced Mechanics: Projectile Motion

Question #1

Question #2

Question #3

Advanced Mechanics: Circular Motion

Question #4

Question #5

Advanced Mechanics: Gravity

Question #6

Question #7

Question #8

Projectile Motion

What is projectile motion?

Let’s break it down. Within the field of advanced mechanics, projectile motion is where objects fall while travelling forwards/backwards/sideways (or not travelling – just falling). In other words, the motion of an object that is thrown or ‘projected’ into the air and then moves under the influence of gravity and air resistance.

This includes understanding concepts such as initial velocity, angle of projection, time of flight, maximum height, horizontal range, and velocity components in both directions.

Need more help understanding this topic? Check out our Guide to Module 5 of HSC Physics for topic summaries, tips and tricks!

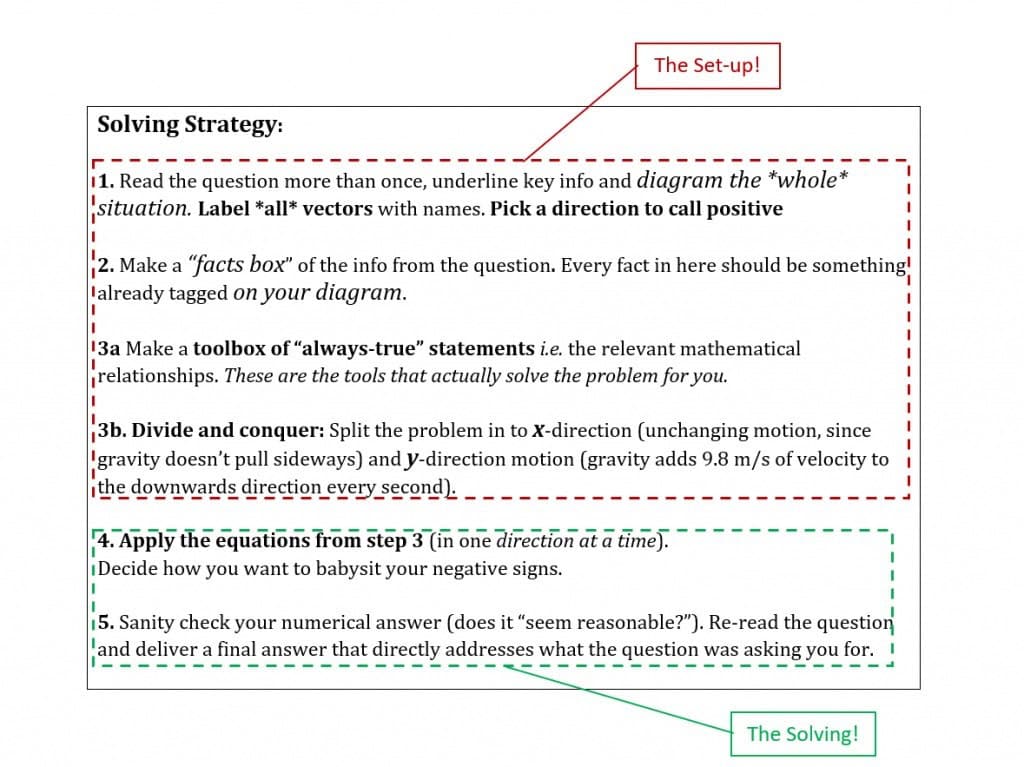

How do you solve projectile motion questions?

Tips

Tip #1: Make your diagram as big and as neat as possible.

Tip #2: Make angles and relative lengths of vectors as realistic as possible.

Tip #3: Stick to what you know is true – assume nothing!

So, let’s dig into some questions!

Question #1

A catapult launches a 2.0 kg rock at 3.2 m/s, 30° elevation, from a 7.0 m high rooftop. How far will the rock have travelled horizontally by the time it’s at the top of its flight?

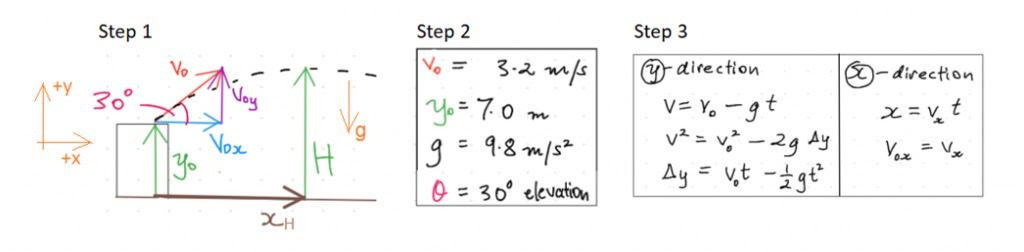

The Set-up:

Step 1: Diagram the whole situation and label everything. Pick a direction to call positive.

Step 2: Make a ‘facts box’ of the question info already tagged on your diagram.

Step 3: Make a box of ‘always true’ statement. Choose how to handle negatives.

It should end up looking something like this:

Note: We took care of negative signs in Step 3 by “pulling the negative” out of g since g points towards decreasing y. Since we’ve already accounted for direction, everything we sub in is positive from now on.

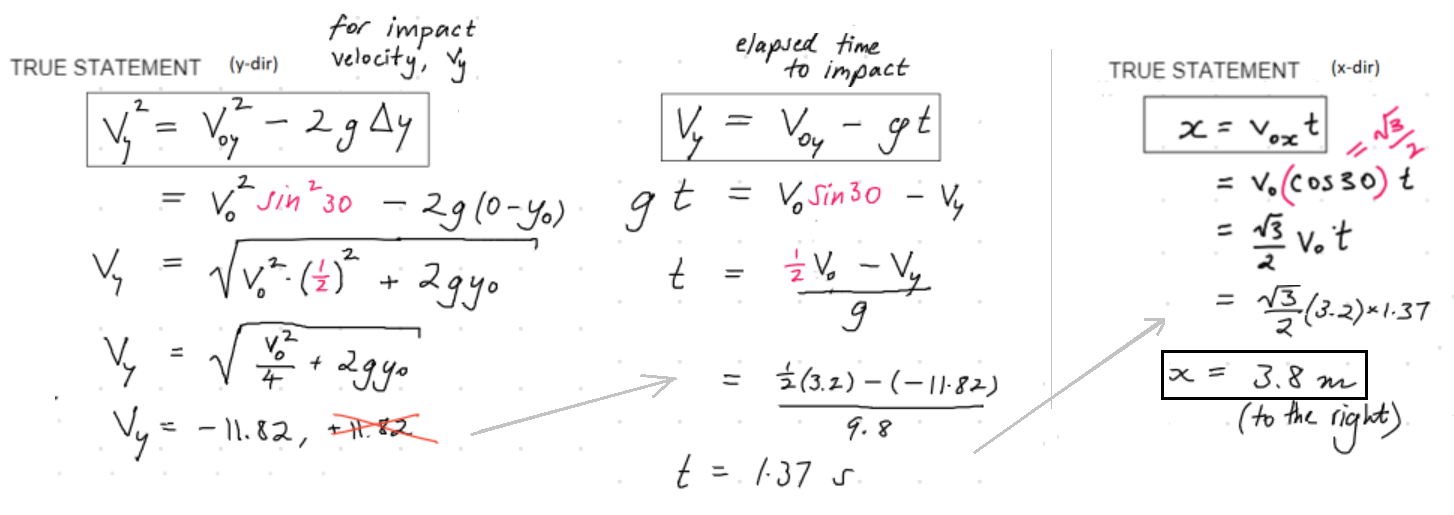

The Solving:

Step 4: The question wants to know about the x distance covered while the rock is on its way up to H.

Let’s pull an ‘always true’ statement out of the toolbox for the x direction and see if it leads us straight to the answer or not:

Not quite! But we already know v0 (from the ‘facts box’) and if only we knew tH (the time taken to get up to H), we’d have the answer in our hands.

But we can’t apply anymore ‘always true’ statements in the x direction, so let’s scene shift to the y direction:

Let’s take the first relation in the “always-true” toolbox for the y direction. It has t in it (the thing we’re trying to find out) and it looks like it’s going to fall apart in to something easier!

Projectiles arriving at the top of their flight must stop going upwards before turning around to fall. At the very moment of being at H (let’s call that moment tH), vy = 0.

In projectile motion, look for equations that are going to fall apart in to something easier (often this means equations where you can make something zero).

What were we saying before? “If only we knew t, we’d immediately know the answer”

The Solution:

Step 5:

Sanity-check: Gravity removes 9.8 m/s of velocity from the upwards direction every second.

It’ll remove 3.2 m/s of upwards velocity in less than a second i.e. the rock should be at the top of its flight very quickly and won’t have had a chance to displace very far forwards.

Answer: The rock will have travelled 0.45 m horizontally by the time it’s at the top of its flight.

Question #2

In the previous question, determine the total horizontal displacement.

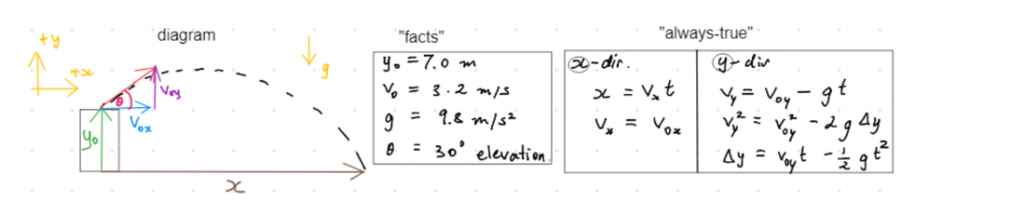

The Set-up:

Note the clearly-stated positive direction for x and y; Also, negatives handled already in the equations (so all inputs will be positive, i.e. g = 9.8 m.s-2)

Once you’ve set-up, apply ‘always true’ statements to the x and y directions independently:

The Solution:

Sanity-check: The cannonball should spend more time falling than it spent rising up (since it falls below/past its starting height). It should have displaced more than twice 0.45 m (i.e. 0.9 m), but not dramatically further. 3.8 m sounds totally reasonable.

Answer: The total horizontal displacement of the rock is 3.8 metres to the right.

Question #3 (Challenge Question)

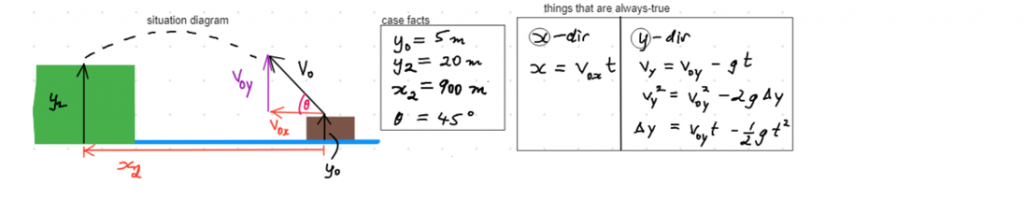

A cannonball is fired from sea at 45° elevation, impacting on land ashore (20 m above sea level, 900 m away). If the ship’s cannon is 5 m above sea level, what was the magnitude of the launch velocity?

The Set-up:

The Solving:

Let’s put an ‘always true’ statement down in the x direction and see where it leads us:

The thing we want to find is v0 (and we already know x2 from our ‘facts’ box), but t2 is going to be tricky to find). That’s as far as we can go in the x direction for the moment.

Put an “always-true” statement down in the y direction and see if that goes anywhere:

Another Roadblock: t2’s the problem again. If only we could ditch t2, we’d be there…

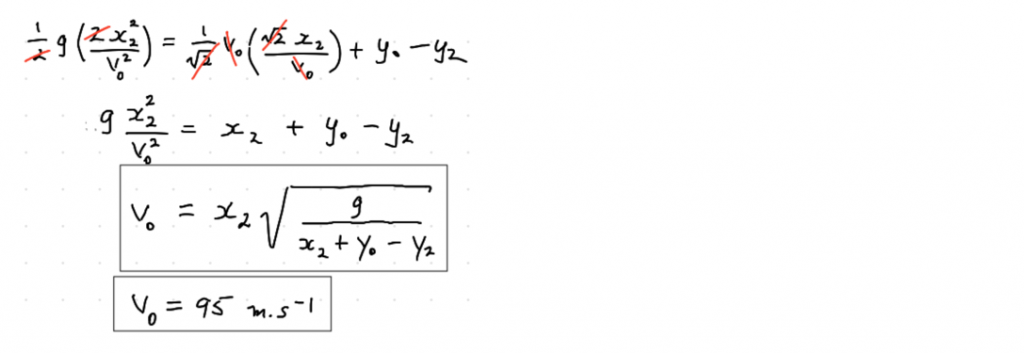

From our work in the x direction, we can re-express t2 (the only thing we don’t know in the above equation) in terms of things that we either already know (x2), or want to find-out as the end-goal (v0):

A-Ha! If we put *that* in for t2 in our y direction equation:

The only thing we won’t know now will be v0 (the thing we’re trying to find out):

You don’t have to bother yourself with restating the direction because the question only wants to know about the “magnitude” of the initial velocity.

The Solution:

Sanity-check: This is about 340 km/h: Reasonable for a cannonball travelling almost a kilometre.

Answer: The initial launch speed of the cannonball is 95 m/s.

What’s important to remember about tackling projectile motion problems?

Lesson #1: It will often not be immediately clear how to proceed.

The key is in laying-down those ‘always true’ statements about the going-ons in the x and y directions. Stick to these ‘always true’ relationships and assume nothing. Stick to the script.

Lesson #2: Experience is a huge factor.

How do you become expert at anything? Trip over it enough times that you’ve got it mastered!

If someone can solve a particular exam question and you can’t, it’s often the case that they’ve had the experience of being unable to solve that type of question before exam day (whereas you’re having that experience for the first time in the exam).

Burn through as many practice questions as you can get your hands on. Get experienced.

Want to get started? Check out our Master List of HSC Physics Past Papers and bookmark it for the future!

Circular Motion

What is circular motion?

Circular motion is where objects swing around in circles (or briefly do part of a circle). Altogether, it refers to the movement of an object along a circular path. It involves concepts such as centripetal force, angular velocity, and acceleration in advanced mechanics.

Objects in circular motion experience a force directed towards the centre of the circle, known as the centripetal force, which keeps them in their curved path. This topic is often studied in the context of understanding the motion of objects like satellites orbiting planets, cars navigating curves, or even amusement park rides!

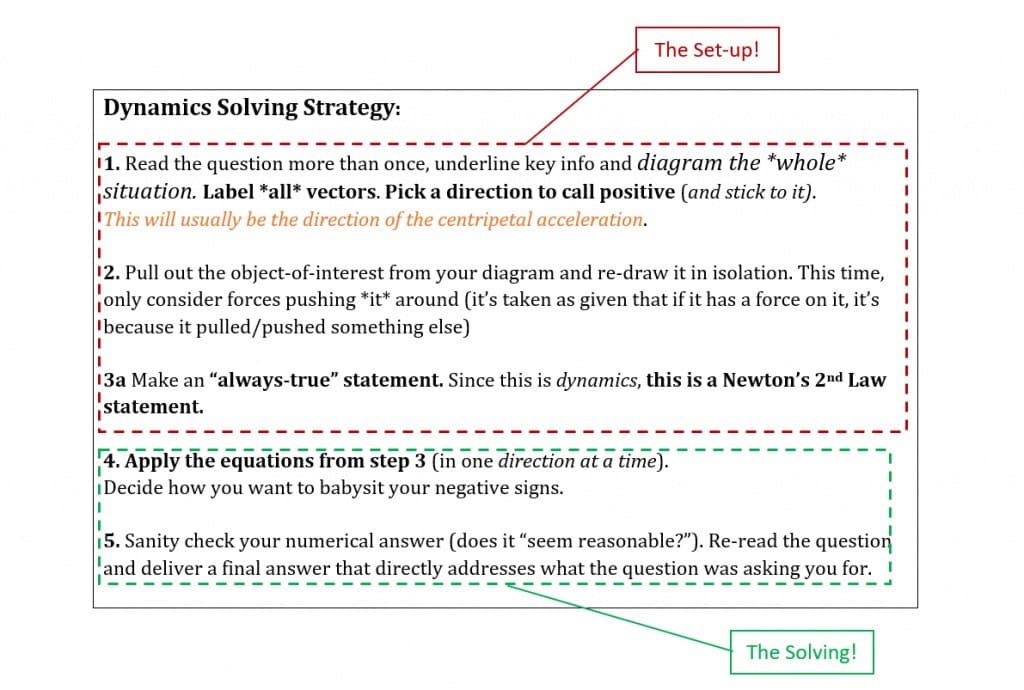

How do you solve circular motion questions?

Tips

Tip #1: The key to decoding every question in this topic is making a correct Newton’s Law statement as your ‘always-true’ key.

Tip #2: Let your brain swim in YouTube videos about Newton’s three laws until you’re absolutely confident that you understand them – they unlock this topic.

Newton’s Laws in Everyday Language

First Law

Things keep doing whatever they’re doing (in straight lines) until an unbalanced amount of force acts to make them change what they’re doing.

You don’t need to push something to keep it moving – in fact, you need to push it to make it stop moving (if it’s already moving).

Pushes/ pulls are needed to *deviate* objects out of their straight-line status quo!

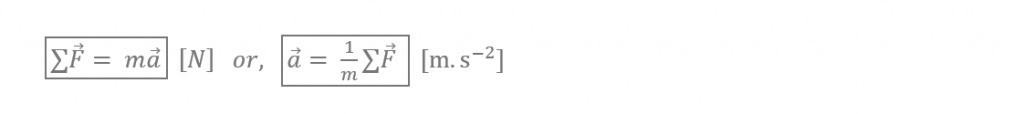

Second Law

Look closely – When a rigid object feels an unbalanced amount of force (and changes its motion), all the individual atoms change their motion together.

The force gets rationed out to all atoms present. If there’s a lot of “stuff”/matter in an object, the Newtons get spread thinly (each atom receiving a lesser share) and the atoms in the object (all together) accelerate less; Massive objects respond less to the same force.

Mass measures force-insensitivity. Mass *is* inertia.

In circular motion, Newton’s 2nd Law is just this:

Third Law

“Every action has an equal and opposite reaction.”

Erase this from your brains. Erase it!! Replace it with this:

“If an object ever feels a force, it’s because it pushed something *else* just as forcefully (the other way). The response depends on mass.”

The forces are equal (and always acting on different objects – there are always two objects involved in any force situation).

The two objects push apart with the same Newtons, but the actual “reactions” (motion change) of the individual objects are determined by their masses/inertia.

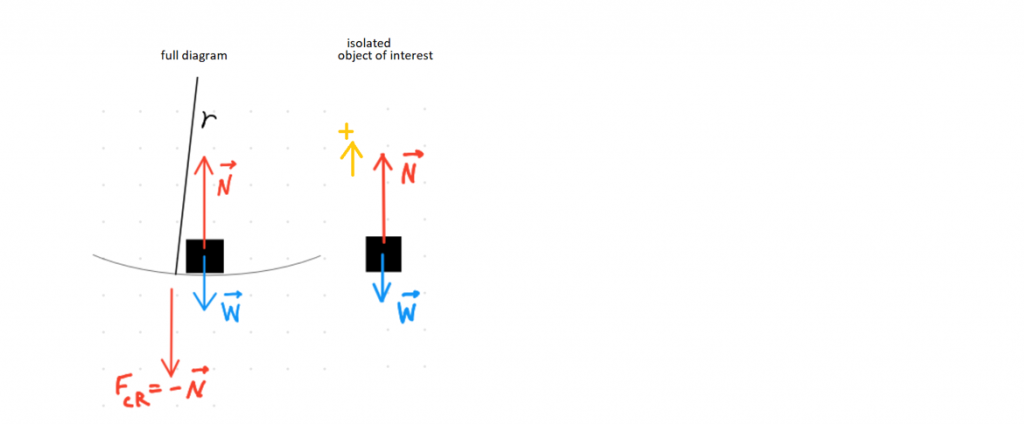

Question #4

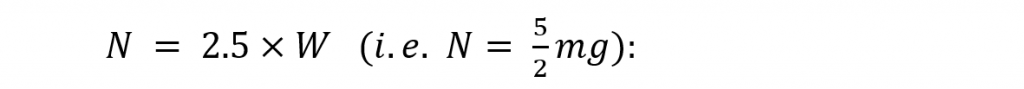

A new road takes cars down one side of a valley and up the other side. The lowest point is a circular arc (radius of curvature: 30 m). What speed limit should be assigned to the stretch of road (50, 60, 80, 110 km.h-1) so that that maximum amount of normal force experienced by drivers is not more than 2.5 times their weight?

The Set-up:

Let’s make a Newton’s Law truth statement along the centripetal-direction:

Remember: It’s the net-amount of force acting centripetally that curves the motion in to a circle (in the same way it’s the net amount of linear force that leads to linear acceleration).

The question wants to know what happens when:

The Solving:

The Solution:

Sanity-check: Answer is within the range needed to answer the question.

Answer: Hence a speed limit of 60 km.h-1 is needed, since 80 km.h-1 would require a normal force corresponding to more than 2.5 g’s.

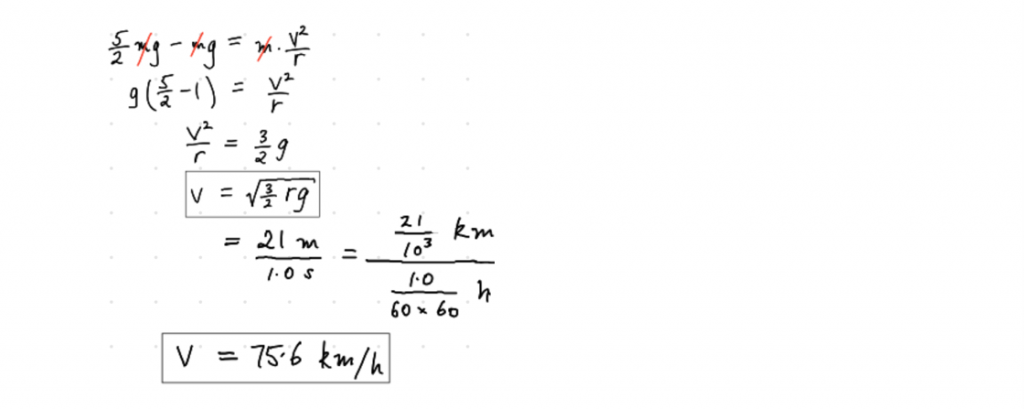

Question #5

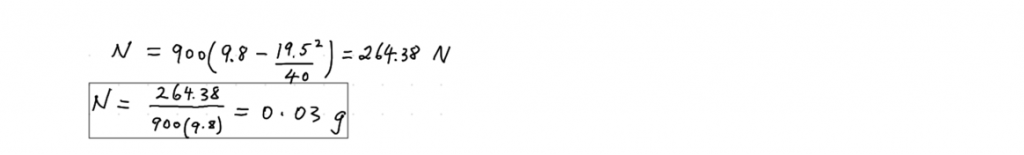

A (900 kg) race-car drives over a rounded hill section (radius of curvature: 40 m) at 70.2 km.h-1. Determine the magnitude of the normal force, N, on the car, at the apex (in g’s).

The Set-up:

There’re really only two options:

- Either the car’s fixed weight force has insufficient pull to stick it to the curvature and it tends out towards a higher radius (i.e. it gets airborne, in the direction of its inertia, with no normal force);

- or N covers up the right amount of W, so that what’s left over is the right number of Newtons: Either way, expect N < W.

The Solving:

State Newton’s 2nd Law in the centripetal direction.

Note: We already handled the negatives at the start (-N), so g = +9.8 m/s2.

The Solution:

Sanity-check: As expected, N < W. Consistent with experience of driving over hills.

Answer: The normal force on the car corresponds to 0.03 g.

Gravity

What is gravitational motion?

Let’s put it this way – gravitational motion refers to where things swing around planets in circles while falling gravitationally. In other words, the study of objects in motion under the influence of gravity.

This includes understanding advanced mechanics concepts such as Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation, gravitational force, gravitational acceleration, projectile motion, orbits, and gravitational potential energy.

Question #6

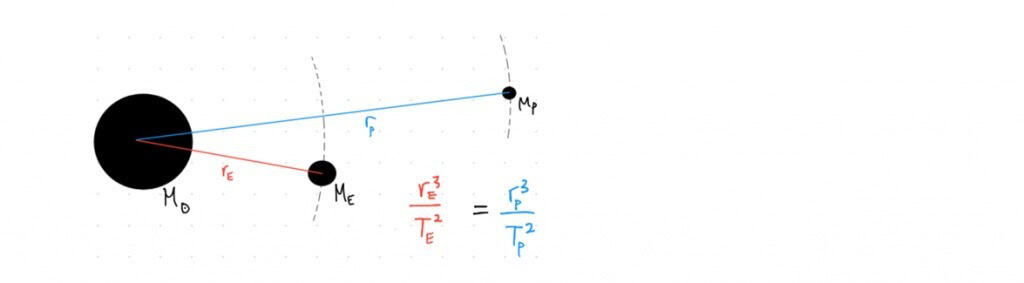

Use the fact that the average Earth-Sun distance is about 1.5 × 108 km to determine the orbital period of Pluto (average orbital radius: 6 × 109 km) in Earth years.

The Set-up:

Step 1: Since this is astronomy, start by creating a hilariously not-to-scale diagram of the situation.

Step 2: Make a statement of Kepler’s Third Law (from your toolbox of ‘always true’ statements).

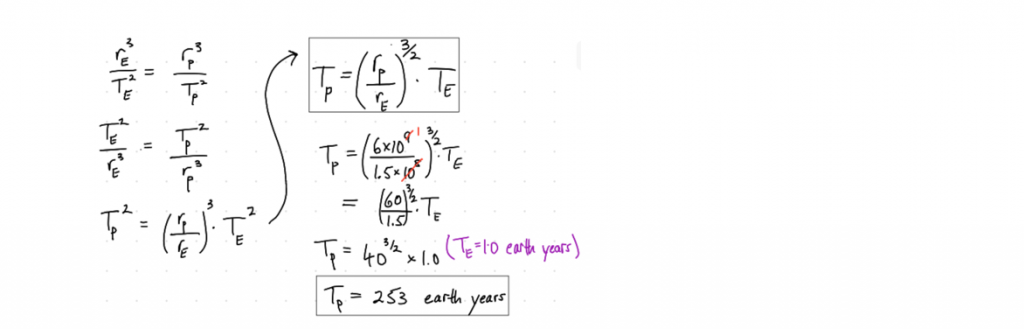

The Solving:

Note: Look closely at the upper boxed-equation above. As long as both radii are in the same units as each other, their units will cancel out (so why other converting them?).

Since T will be determining the units, I can sub it in however I like (in this case, in earth years).

The Solution:

Sanity-check: While the answer means Pluto won’t even get close to doing a half-orbit in your entire life-time even if you live to 100, it’s perfectly sensible physics, as outer solar system objects travel slower and have greater distances to cover.

Answer: The orbital period of Pluto is 253 Earth years.

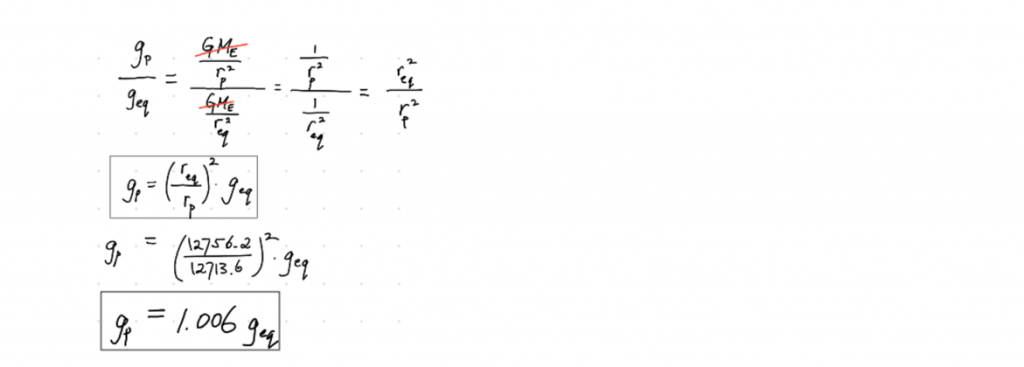

Question #7

The Earth’s pole-to-pole diameter (12713.6 km) is shorter than its equatorial diameter (12756.2 km).

Determine by what percent factor gravity is stronger at the poles compared to at the equator.

The Set-up:

The question wants a direct comparison: In physics, that means numbers. Let’s find the field-strength ratio between the g-fields.

The Solution:

Sanity-check: Totally reasonable. We weren’t expecting any dramatic difference.

Answer: Polar g-field strength is 0.6% stronger than at the equator.

Question #8

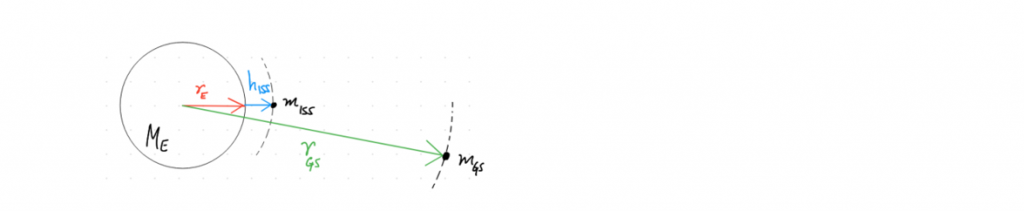

“Compare the International Space Station’s orbital velocity to that of a geostationary satellite, given that the ISS orbits at an altitude of 400 km and the Earth’s diameter and mass are 12742 km and 5.97 × 1024 kg”.

The Set-up:

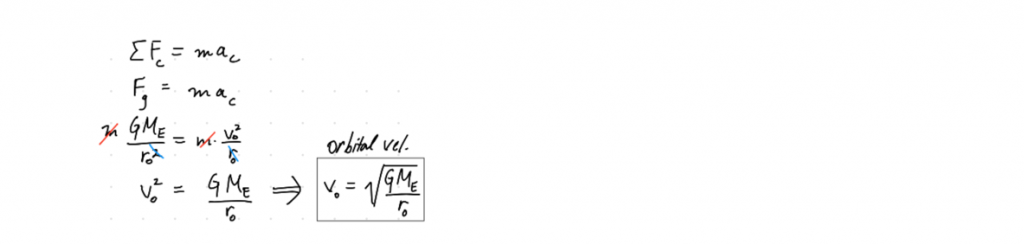

Let’s make a Newton’s 2nd Law statement in the centripetal direction and see where it takes us.

OK! We could compare the orbital speed of the ISS to a geostationary orbit, if only we knew where geostationary orbits actually happen (i.e. if we knew rGS).

The Solving:

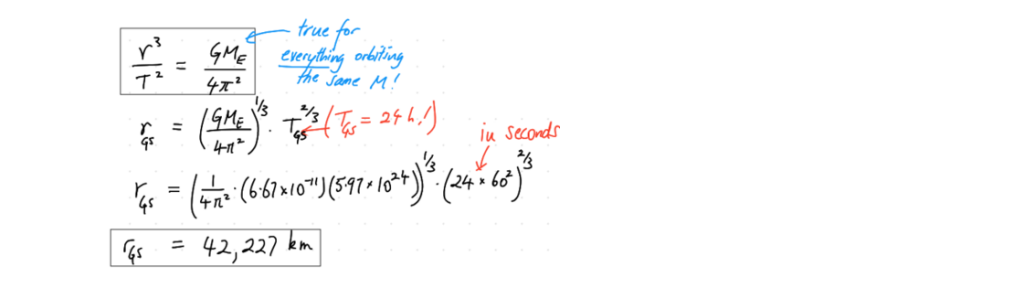

Let’s make another “always-true” statement involving rGS, Kepler’s Third Law.

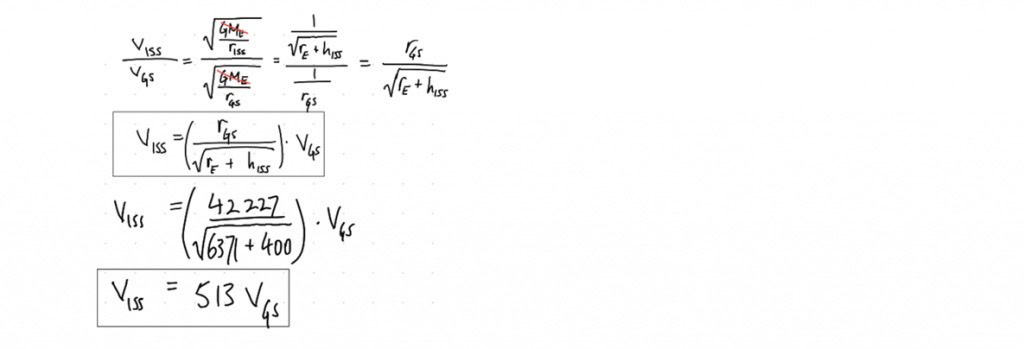

Now we can do the comparison the question wants.

The Solution:

Sanity-check: Closer-in orbits (i.e. 400 km altitude, vs 35856 km altitude) are faster-moving (to balance the greater inwards-pull of gravity there), so this makes sense.

Answer: The ISS orbits at 513 times the orbital velocity of a geostationary orbit.

And that wraps up the last of our HSC Physics Questions for Advanced Mechanics!

When you’re working through questions, always remember to diagram everything out big and neat, only apply tools to questions that you know are true (i.e laws) and get as much practice as possible so you can get experience as a problem solver!

Got your HSC Physics exam coming up? We’ve made a 7-Day Study Plan for Physics for you!

Looking for some extra help with HSC Physics?

We pride ourselves on our inspirational HSC Physics coaches and mentors!

We offer tutoring and mentoring for Years K-12 in a variety of subjects, with personalised lessons conducted one-on-one in your home or at our state of the art campus in Hornsby!

To find out more and get started with an inspirational tutor and mentor get in touch today to boost your marks in Advanced Mechanics and other areas of HSC Physics.

Give us a ring on 1300 267 888, email us at [email protected] or check us out on TikTok!